For three years, British photographer Emily Graham has documented the oldest treasure hunt in the world – still unresolved to this day. In The blindest man, a disconcerting series, she questions the notions of obsessions, interpretation, and the fear of failure known to men. Interview.

Fisheye: How did you discover photography?

Emily Graham: I came to photography whilst I was studying for my A-levels. I went to a grammar school, and my art a-level class was taught in a very traditional way. Frustrated, I started an evening class in photography and loved it. My parents let me set up a darkroom in our garage, and I would spend hours in there in the evenings. This isn’t to say I became a great printer – I didn’t – but the initial pleasure and interest in photography definitely came from taking something from the world, seeing and isolating it, and then coming home to process and print, and seeing it again emerge later as an image.

What is your working process?

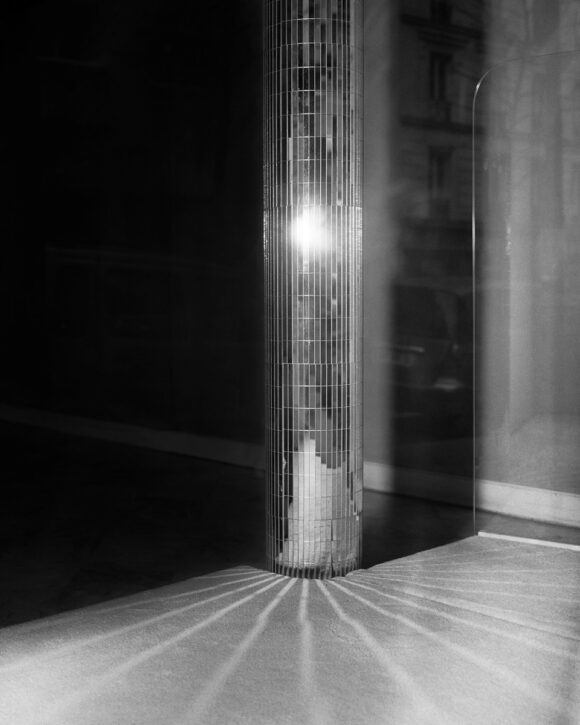

I like to wander with a camera. So much of my work begins by going on walks. I’m interested in how the everyday can be transformed through the photographic act, how interesting pictures can be found in unremarkable places. I work slowly, generally using a camera that allows me to make quite formal pictures, and I’m often watching for where light animates things in a particular way. Photographs themselves can be so malleable, their implied meaning changing depending on context: this is what I love about photography.

Would you define your approach as documentary?

My work is rooted in documentary, but I’m not sure I’d call it straight documentary, as I often use a combination of documentation, construction and manipulation in my work. Someone recently referred to it as crooked documentary, a term which came from the critic Lucy Soutter, who wrote about a more expressionistic, looser kind of documentary practice, and that feels more fitting.

What was the genesis of The blindest man?

The blindest man

is based on the story of a real-life unsolved treasure hunt. This work is about searching and the biases of looking, about people obsessed with their own projects, the difficulties of finding what you are looking for and getting lost in the looking.

The project came about as I realised that I was myself going on walks with specific ideas in mind, due to my research. I started thinking about how much of what I photograph was influenced by what I had in mind and I began to view these trips as a kind of scavenger hunt.

Did you find one that caught your attention?

Yes. I took a literal jump, and starting researching real-life treasure hunts. After a while I came across a hunt in France that was unsolved, and claimed to be the longest running treasure hunt in the world. It was difficult to find clear information online, partly as it was in French (which I didn’t speak), and partly because there was little concise coverage, only many sprawling blogs and 90s-looking chat forums. The information seemed to be contradictory and never-ending.

What did you find out?

The particular details of this hunt are compelling: over 25 years ago, a golden treasure was buried somewhere in the landscape of France, and it is yet to be found. A community of people still searches for the hidden gold, guided by a book of allusive clues, released by an anonymous author. Though said author is now dead, hundreds search on, committing hours, weeks, and years to the hunt. The competition was designed to be solved within a few years, but the community that has developed around it has spread rumour, misinformation and red herrings, confusing individual routes of investigation.

You’ve worked on this project for three years. How has it evolved over time?

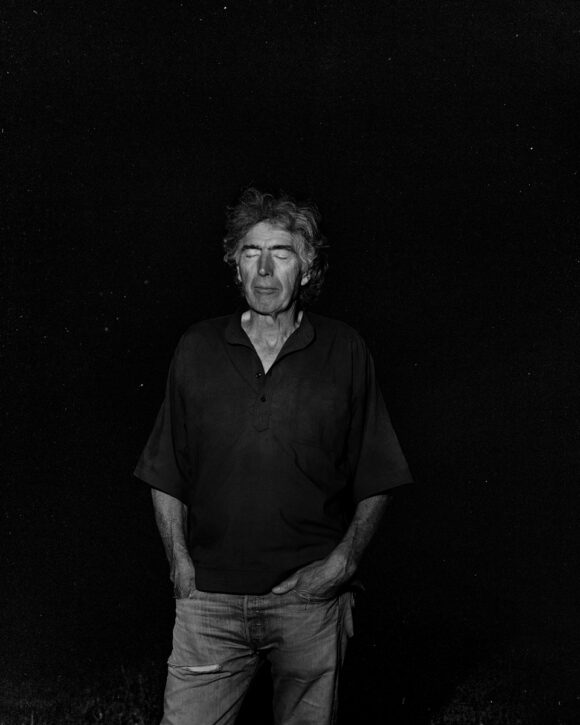

I first joined in this pursuit, following hunters’ failed searches across France. But I was less interested in creating a documentary about the hunt, and more fascinated by the players’ stories. After a while, I began contacting searchers, interviewing them about their experiences looking for this treasure. Talking to them was fascinating – so many of them had vastly different interpretations – and listening to each one I’d be absorbed by their theories. At that point, many people’s response was that it would make a great documentary film!

Why did you choose to use only photography then?

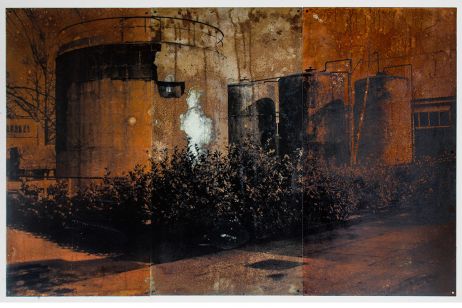

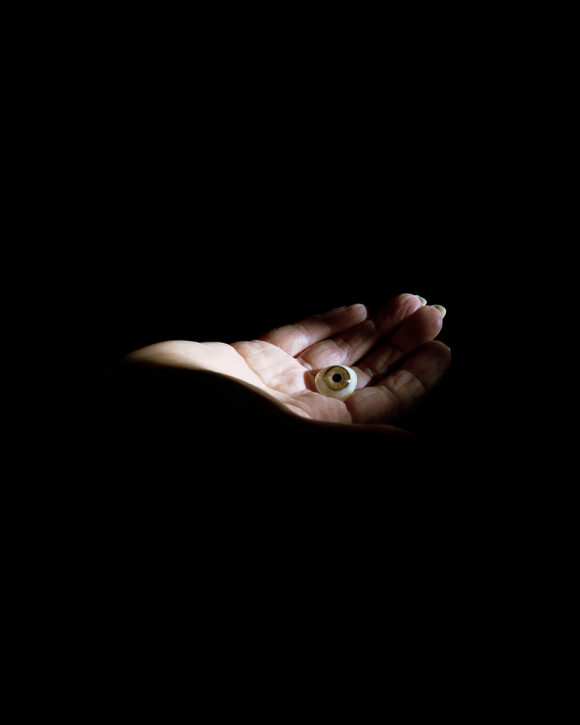

It was exactly the limitations of the photograph that I wanted to play with. There was little to document photographically, as much of the activity of the hunt happens in the minds of the players – rather than manifests as physical activity – but there seemed to be a rich imaginative world connected to the players. I began thinking about the hunt as a metaphor, and I used it to question the nature of pursuit and failure, and in turn, photography’s own slippery relationship to truth, searching, interpretation, fantasy and obsession.

Could you give us examples of these “obsessions”?

One person has a spiritual reading of the quest, and her life has become imbued with signs. Another one day dreams of being victorious and in trying to calculate solutions, in always being on the cusp of finding the thing, is often taken away from his time with his family and friends. Another person had raised a court case against the family of the author (who is now deceased), to halt the search. He posits that he has the correct solutions and the game is fraudulent.

For me, this connects to the ways in which people respond to the difficulties and frustrations they experience. I was trying to make pictures that evoke this space, to have a kind of fever dream quality to them. Light acted as portent, highlighting some details. I was also inspired by the idea of obfuscation: deliberately making things unclear.

Various documents (drawings, maps…) complete your images. What do they represent?

In the hunt, the clues draw on many different types of knowledge and searchers, in their research, as I mentioned, have interpreted the clues in wildly different ways. I wanted to bring some of these bits of research into the book, without explanation, to lead the pictures, to imply narrative but lead nowhere, and in turn create their own connections with the photographs.

Where does the title – The blindest man – comes from?

It comes from one of the clues in the treasure hunt – itself taken from an old proverb: the blindest man is the one who refuses to see. The original proverb is about choosing to ignore what you already know, or not seeing what is right in front of you, which was fitting as a framing for the work!

© Emily Graham