Spanish photographer Jordi Ruiz Cirera presents, at the Circulation(s) Festival, Los Menonos, a documentary project dedicated to Mennonites, a community living peacefully, far away from the modern world. Interview.

Fisheye: Can you introduce yourself?

Jordi Ruiz Cirera: I am a photographer and director from Barcelona, and currently based in Mexico. Over there, I work on long-term projects, often inspired by the migrations in the region.

What has been your photography path?

I started off as self-taught, by trying out different cameras, and then I enrolled in a Master at the London College of Communication in 2011. Since then, I have been working as a freelance photographer, by producing personal projects, such as Los Menonos, exhibited at Circulation(s) — which was actually my first long-term project — as well as commissions for medias, NGOs or societies.

How do you start off your projects?

I have a documentary approach, and I like spending time with my subjects. However, my way of proceeding has changed greatly over the years. I used to stay as much time as possible in one place, trying to blend in the background, in order to capture daily life as it unfolded around. Although I still think of this approach as most effective one, sometimes, times does not allow for it. So I chose to carry only one medium format film camera with me, which allows me a different form of closeness with my subjects.

Can you tell us more about the Mennonite community, the subject of your series Los Menonos?

Several Mennonites communities exist, all based in the Easter part of Bolivia. They came from Canada, Mexico and Belize and immigrated in the 1950s — for various reasons, they could not continue living the way they wanted there. The Mennonites live without modern utilities: they do not use cars, telephones nor computers. They lead a peaceful life, quite removed from the contemporary societies.

How did you get the idea to work on this project?

I started working on this project out of curiosity. I wanted to try to understand why a community as big as theirs would choose to live “off-the-grid” and refuse any form of modernity. After learning about their existence, I was tempted to document their daily life. I spent around a month within those communities, and I came back one year later. Most of the images exhibited at Circulation(s) were taken during my second trip. It was at that moment that I had the idea of doing a series of portraits, in order to showcase the Mennonites communities in a different way.

What way?

I went to Bolivia for the first time in 2010, before starting my studies in photography. In 2011, during my masters, I discovered a lot of “traditional” news coverages on other communities. Although they seemed interesting, they were not offering anything new. I then thought about producing portraits. They can be shown independently from the rest of the series, which allowed me to document the Mennonites’ reality. By observing them — their clothes, their physical appearance, their homes, their sun marks… — we become aware of the importance of the notion of community in their daily life.

What have you learned from your trips? How did they welcome you?

By observing them and talking to them, I learned that their daily life is governed by the Mennonite faith, which takes the form of dogmas that can hardly be questioned. I realised that they lead a very peaceful life, and I even tried to adjust to that rhythm.

I have always respected their privacy: if someone did not want to be photographed, I respected their wishes. But the community was rather curious of me. They would ask me where I came from, who I was… Few strangers come to meet them, and they all seemed interested in my project.

Mennonites are not allowed to take pictures. Did this affect your approach to the subject?

It is true that photography is prohibited for them. Nevertheless, they all reacted differently to my presence. Some claimed that I was forbidden to photograph them. Others confided that although they couldn’t take pictures, I was free to do so. A man explained to me that I was allowed to use my camera, but only if I captured him in a candid way: I couldn’t take a formal portrait of him. In general, the members of the community were rather shy. Therefore, I took my time to get to know them before photographing them.

Did anything surprise you, during your stay?

Since it was all new to me, I remember being constantly surprised during my visits there. But I especially remember their tranquility. They all seemed to have a pleasant life, all the while knowing exactly what their future would be. It seemed to me that they were not as anxious or worried as more modern societies, who cannot foresee their life in the same way.

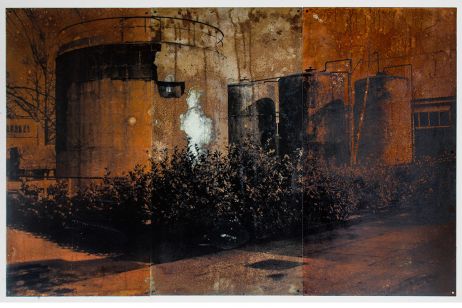

© Jordi Ruiz Cirera