Fisheye: Can you describe the genesis of this project?

I first visited Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2011, where I stumbled across a young street-prostitute prospecting along the Mekong River. I became struck and ultimately haunted by the look of despair and desolation in her eyes. I returned home to Sydney, Australia, and did research on sex slavery in Phnom Penh. Prior to returning I emailed two of the largest NGOs in the region for some advice, but frustratingly received no reply, so further down the rabbit hole I dived. I wrote down the names of the infamous areas of Phnom Penh and upon arriving in Phnom Penh I got on the back of a motor bike of a friend and told her to take me to these places. Every one of those places, she told me not to go alone or to go there at night. I did both. I stayed initially for twenty-one days. From memory it wasn’t until the last week that I walked into the (at the time unknown to me) brothel housing trafficked women.

At what point were you personally involved? To what extent can we find you inside the pictures?

The moment I take any photograph, I become personally involved. I also believe every photograph of this nature, to a degree, is a self-portrait. My photos are my letters to the world that I don’t have the skill to write.

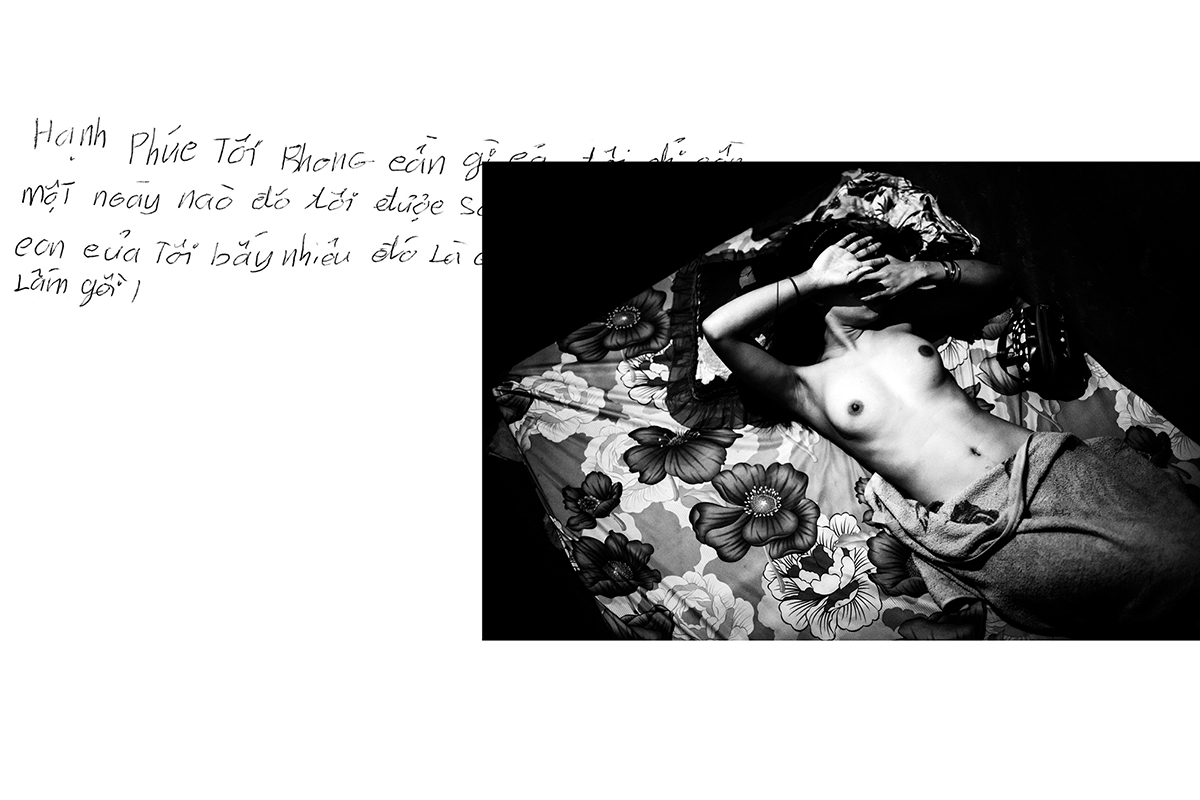

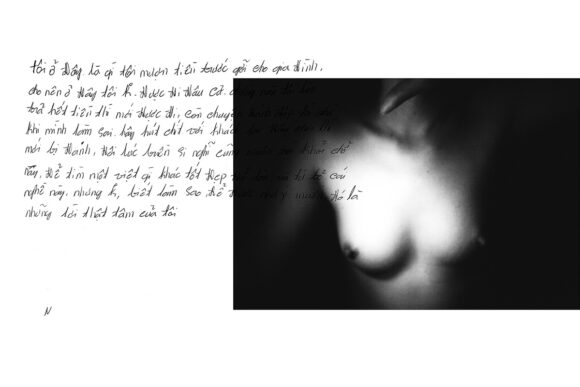

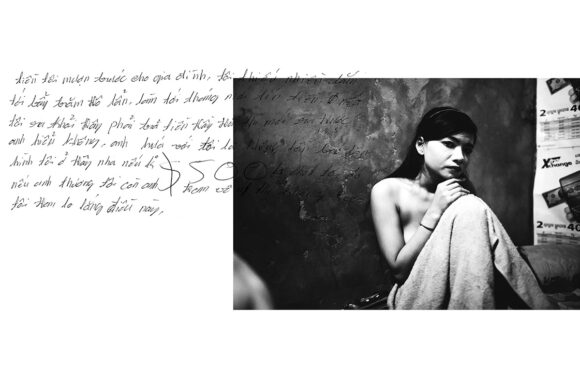

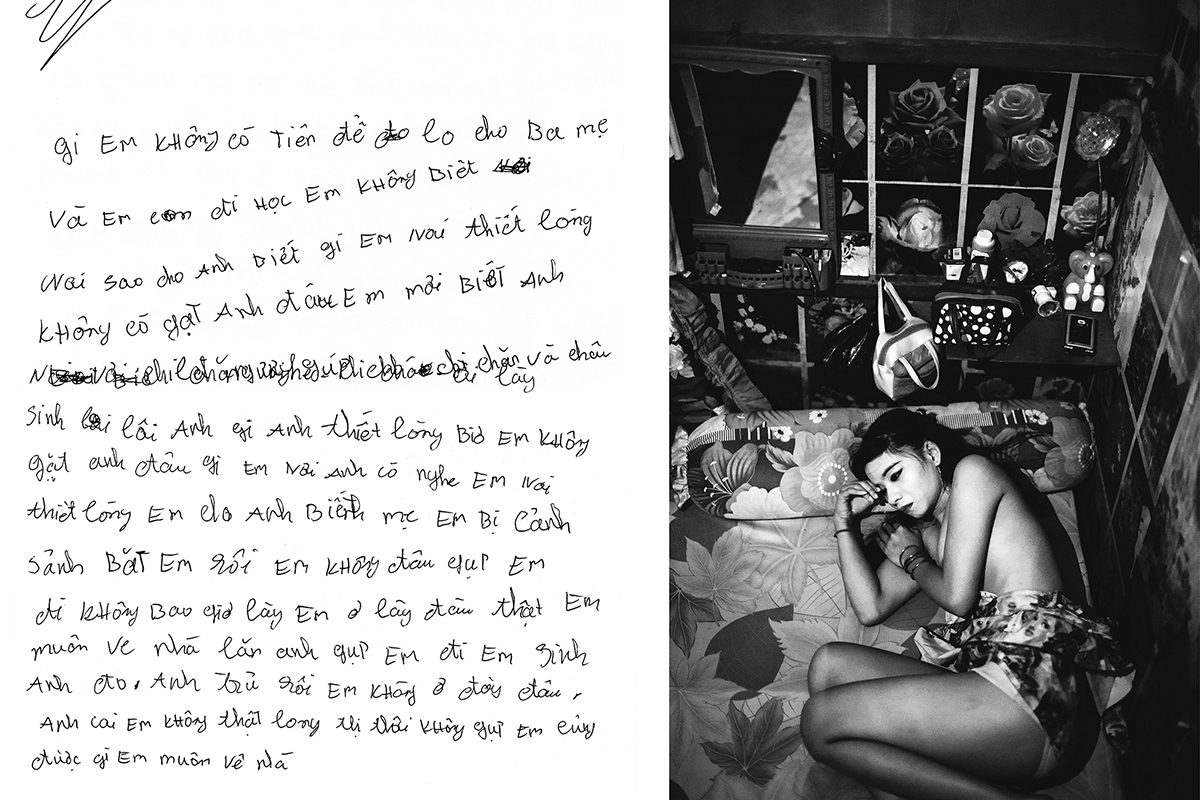

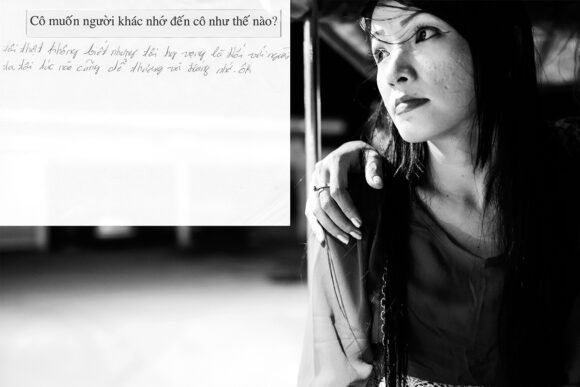

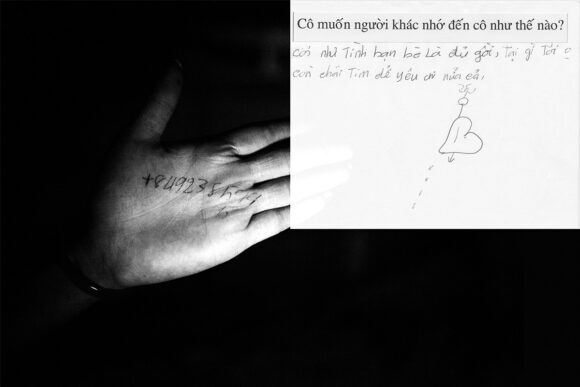

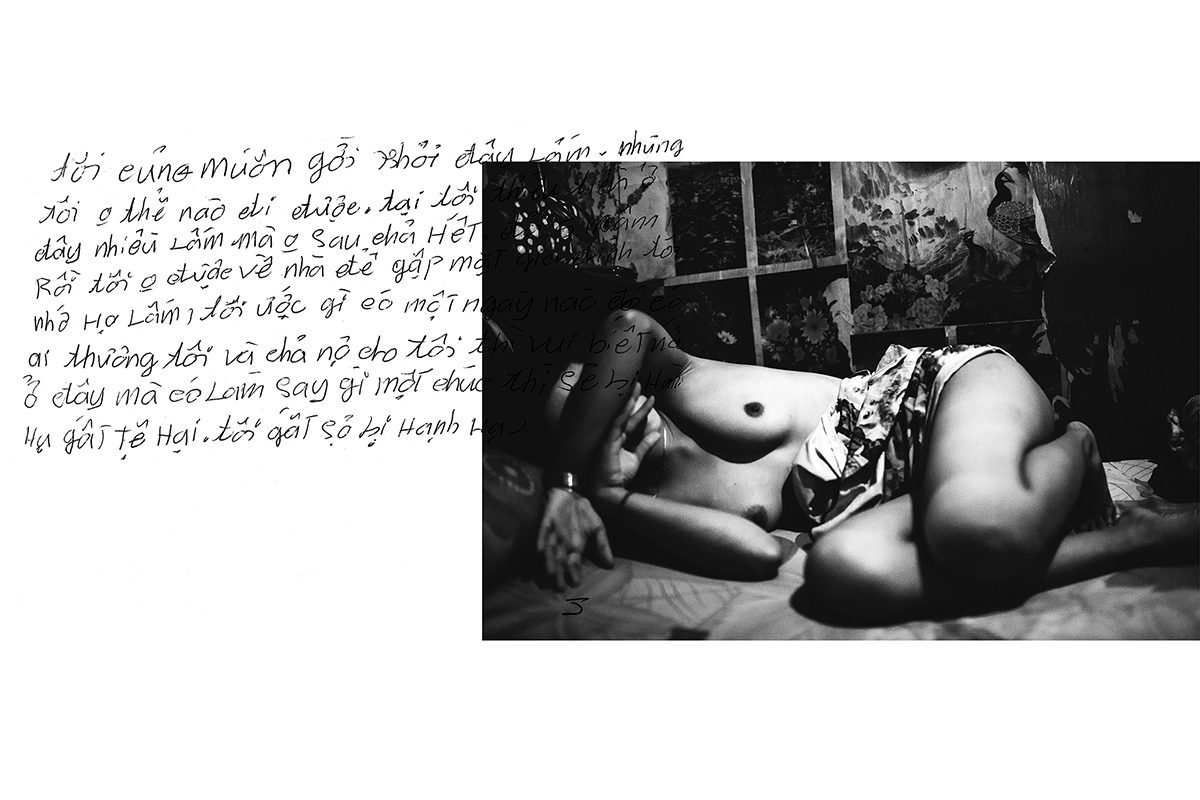

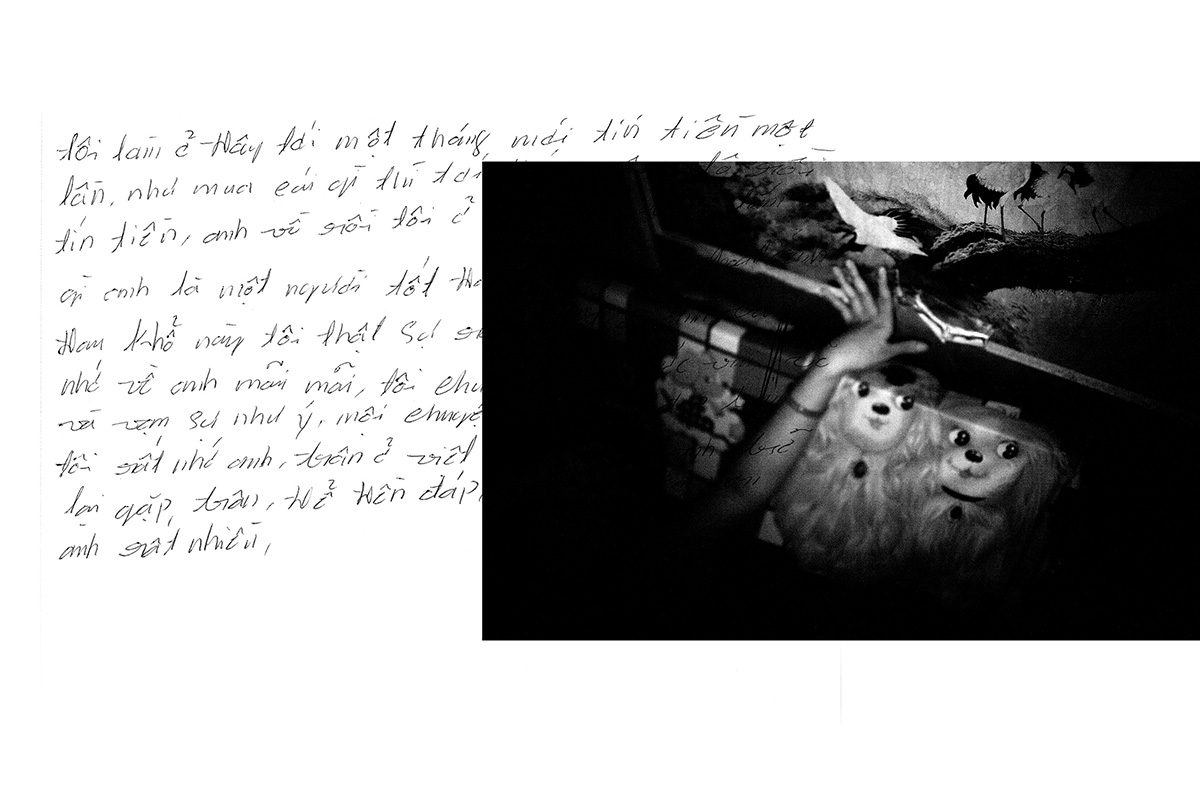

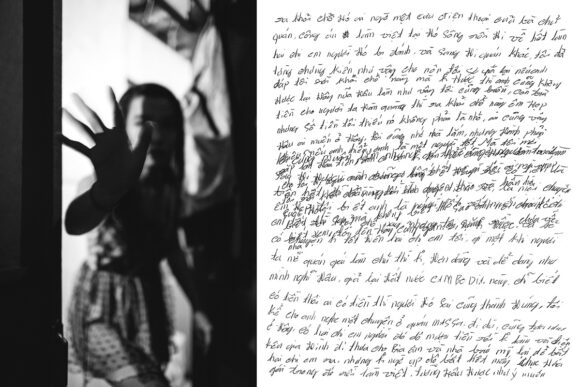

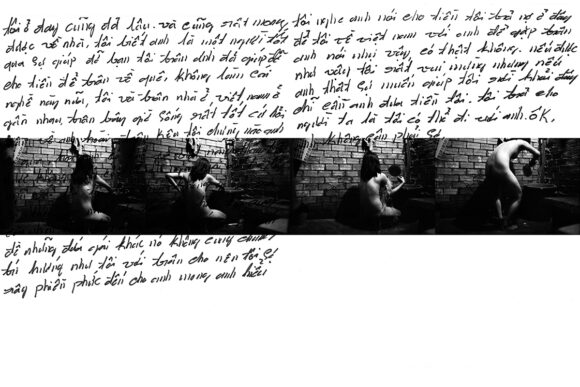

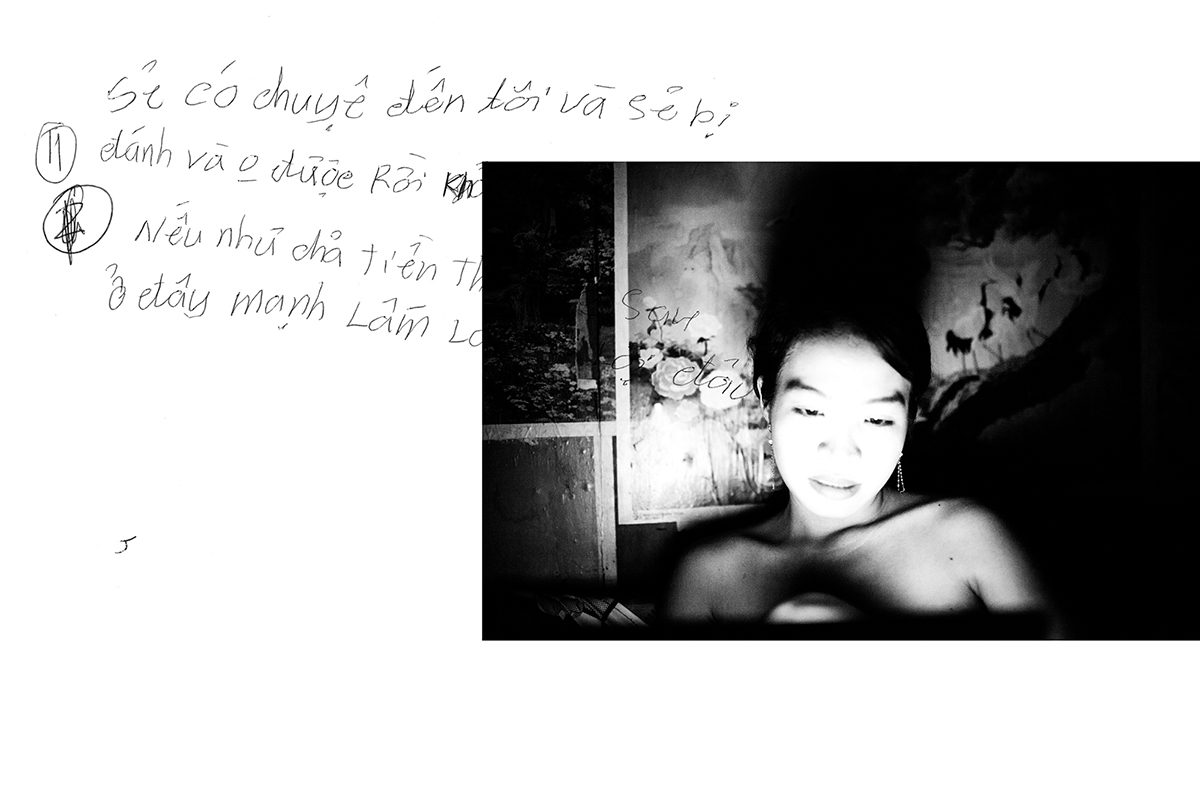

Can you elaborate a little on your choice to have bits of the women’s own hand-writing on the pictures?

The hand-writing is as important as the photograph. Having the text as a part of the photograph is giving the women their voice, their message to us, the viewer, in no ambiguous terms. Due to the sensitivity of this topic, having the words as part of the photograph dramatically changed the narration of “By the River.”

What lessons did you get out of this project, and what do you think people can learn through your work?

I never want my work to give answers. I don’t see art that way. Art for me should always be a question mark. It’s up to the viewer to get what they get from it. What matters to me, and always has, is the feedback from the women and the people from the NGO who guided me over the 3.5 years.

I hope that through my work people understand that it’s okay to be uncomfortable, and to be challenged on what they believe to be right or wrong.

No NGO wanted to help me initially, my local friend told me never to visit the bad areas, and even when I reached out to another NGO they told me they weren’t interested in the brothel. Also, my boss in Australia needed me and didn’t want me to leave, so he asked me” Are you willing to lose your job over this?” I replied, “Yes I am”. So, from a photographer’s stand point, dedication and not luck is something people can learn from this.

Your photographs pushed the NGO to rescue eight sex workers and three kids, and to prosecute the traffickers. How powerful do you think photography can be in terms of social action?

Photography is the most powerful form of art in the world in relation to social change. A powerful photograph can instantly change public and even global opinion. History has proven that with works by the likes of Eddie Adams, James Nachtwey and Nick Ut. I’ll never forget the vulture photograph by Kevin Carter, for example. My photos will never be in that category of icon or status, but my photographs led to a profound change in the lives of three children and to a lesser degree, eight women.

What is photography to you? Why did you decide to become a photographer?

When I have my camera, I feel fearless. Fearless to explore all those places I’m told not to go. Where it’s dark, my camera is my light. I don’t know of anything else that can help me explore my desires and fears like photography. Nothing scares me more than what I want most – love, companionship, and I’m discovering my photography is drawing me to people who, for the most part, don’t say no to me.

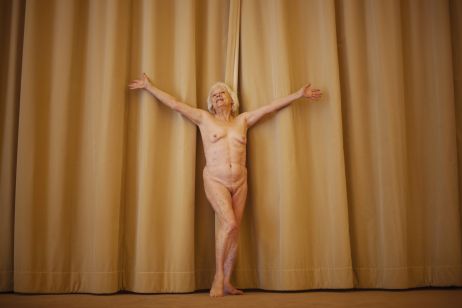

This is not the first time you do a photographic project on sex-workers. What is it that pushes you to focus on this world?

It’s the alluring nature of sex and death. The sex workers I am drawn to tend to be on the brink – or the edge. As to why I want to photograph them, it’s their drive to live on, to find purpose in where and who they are. I find that incredibly revealing and inspiring. For my next project I’m going to attempt to document transgender sex workers in the notorious red-light areas of India.

Why this title, “By the River”?

“By the River” has a layered representation. The title reflects the pseudo-romanticism and fleeting hope I felt and encountered over the 3.5 years. It was the first title I thought of from the moment when I stumbled across a young street-prostitute prospecting along the Mekong River – by the river. This young woman was the reason I came back to start a project on prostitution in Phnom Penh.

Images by © Ian Flanders